Why Peer Support Matters: Empowering Parents to Navigate Mental Health Challenges

“Parents are the first responders in a youth mental health crisis, but who supports them? This research reveals why families are critical to help-seeking, the barriers they face, and how parent-focused interventions like peer support can transform outcomes for both young people and their carers.”

-

1.1 Summary

CYP (children/young people) experience high rates of mental health difficulties, yet access to care is limited. Families are critical in help-seeking, but parental stress, low mental health literacy, and systemic barriers can hinder engagement. Evidence shows that parent-focused interventions (e.g. psychoeducation, peer support, and family-inclusive approaches) improve both parental wellbeing and youth outcomes. EPIC’s programs exemplify these principles, providing accessible, practical support to parents while strengthening the capacity of young people to access care.

1.2 Introduction

Mental health difficulties are common among children, adolescents, and young people (CYP), with approximately half of all conditions emerging before age 14 and most before age 18. Anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and substance use are among the most prevalent, with young women and LGBTQIA+ youth disproportionately affected. Despite the high prevalence, many CYP face barriers to accessing care, including stigma, limited service availability, long wait times, and low mental health literacy.

Parents and carers are central to recognising difficulties, facilitating help-seeking, and supporting ongoing care. Their knowledge, beliefs, and emotional availability influence whether, when, and how CYP access services, while their own wellbeing is impacted by the demands of caregiving. Interventions that support parents, such as psychoeducation, family-inclusive approaches, and peer support, can improve parental mental health, strengthen parent-child relationships, and ultimately enhance outcomes for CYP.

This report summarises current trends in youth mental health, access to care, parental influence on help-seeking, and support needs for families, highlighting evidence-based strategies and the role of peer support programs such as EPIC in improving outcomes for both CYP and their carers.

-

2.1 Common conditions and age of onset

Young people experience the highest prevalence of mental health disorders compared to any other life stage(1). The Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022)(2) in their National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing highlight a range of findings. 38.8% of people aged 16–24 reported living with a mental health condition (significantly higher than any other age group), with one in four seeking professional support and over a third reporting that they did not receive the counselling they needed.

Anxiety disorders are the most common, affecting approximately 82% of young people with a mental health condition. These include generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Affective disorders, such as depression, dysthymia, and bipolar disorder, affect 35%, while substance use disorders (including alcohol and drug misuse) affect around 20% of young people.

Globally, around 50% of all mental health conditions begin before age 14, and 75% emerge before age 18. Anxiety symptoms typically emerge in late childhood to early adolescence (ages 8–14), while depressive symptoms often develop during mid-to-late adolescence (14–18 years). Eating disorders commonly onset in adolescence, particularly among young women aged 13–19, while ADHD and neurodevelopmental disorders usually appear earlier, during primary school years.

Gender differences are pronounced: 45.5% of young women report a mental health disorder compared to 32.4% of young men. Young women also experience more than double the rate of psychological distress (34.2% vs 18.0%). Males are more likely to experience substance use disorders, while females experience higher rates of anxiety and affective disorders. LGBTQIA+ youth are disproportionately affected, with 58.7% reporting a mental health disorder—almost three times the rate of heterosexual peers.

Despite Australia’s reputation as a global leader in youth mental health reform, population-level distress has continued to rise. Rates of psychological distress among young people have increased by 5.5% over five years, with nearly one in five aged 11–17 experiencing high or very high distress. Suicide remains the leading cause of death among children and adolescents aged 5–17.

-

3.1 Overview of access to mental health care

Access to mental health care for children and adolescents is shaped by a complex interaction of individual, relational, and systemic factors. Although help-seeking can reduce the severity and persistence of mental health problems and promote recovery, (3) many young people continue to experience difficulty obtaining timely and appropriate support.

In Australia, mental health care is delivered through a mix of public, private, and community services, depending on the specific needs and resources young people have available to them. National data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics in 2022(4) indicates that mental health service utilisation only consists of around half of those who have struggled with mental health disorder in the previous 12 months (45.1%), with many either unaware of available services or unable to access them due to cost, long wait times, and limited local options.

Families and young people also face perceptual and structural barriers that limit engagement.(5) Common obstacles include a lack of information about how to seek help, concerns about being dismissed by healthcare professionals, stigma surrounding mental health, and dissatisfaction with short or impersonal appointments. Services for youth provided by Headspace have reported overwhelming demands and growing concerns surrounding wait times (approximately 10.5 days for intake, 25 days for first session).(6) A recent Australian study highlighted wait times for anxiety and depression being approximately 99.6 days, with long wait times associated with increased psychological distress and worsening mental health.(7) National initiatives have sought to combat this through developments such as additional subsidised medicare psychological therapy sessions and reduced costs to common medications (i.e. the Better Access initiative), though there exists a continuing gap in access.

Access to care for young people is not merely a logistical issue but reflects how young people conceptualise help, who they turn to, and whether systems respond effectively. Addressing these gaps requires coordinated reforms that enhance service availability, improve information flow, and build supportive relationships between young people, their families, and professionals. These access dynamics provide the foundation for understanding adolescent help-seeking behaviour, discussed in the following section (3.2).

Referrals, wait times, and access barriers

A combination of social, family, and systemic factors contribute to worsening mental health in young people. Socioeconomic disadvantage, family conflict, academic stress, stigma, and limited service access are among the most influential risks.(8) Youth from low-income households experience higher rates of depression, anxiety, and substance misuse, often compounded by housing instability and reduced access to early intervention .

Service barriers remain a critical issue. Despite rising rates of distress, many young people struggle to access appropriate mental health care. Research shows that up to 75% of adolescents with mental health problems are not in contact with services, with long wait times, limited referral pathways, and high service thresholds preventing early treatment.(9) Referrals to specialists or inpatient units are often delayed due to workforce shortages and fragmented coordination between primary and specialist care. These delays can allow symptoms to escalate before support is provided.(10)

At the family level, parental mental health and emotional dysregulation can heighten youth distress, creating reciprocal cycles of stress, further discussed in section 4.2.(11) Social media exposure, identity-based discrimination, and academic pressure also contribute to elevated anxiety and depression.(12) -

3.2 Adolescents and help seeking

Help-seeking is central to addressing mental health challenges in youth, as it connects adolescents with the support they need. However, professional services are not the only source of help—informal support, including friends, family, and school staff, play a substantial role. Data from the Young Minds Matter Survey shows that 63% ofadolescents rely primarily on informal support.13 While these networks can facilitate access to care, they may also obstruct help-seeking, for example through dismissal of concerns, fear of punishment, or trauma being normalised in families.14

Models of Adolescent help seeking

Rickwood and Thomas (2012) define mental health help-seeking as “an adaptive coping process”,(15) occurring when internal or external coping resources are exhausted. High levels of psychological distress increase the likelihood of seeking professional help, yet many adolescents in urgent need do not access support.(16) Barriers include introversion, low perceived benefit, unfamiliarity with mental health services, a desire for self-reliance, and systemic obstacles.(17,18) Gender also influences help-seeking: males are less likely to seek help than females,(19) often relying on friends and family, while females more frequently engage professionals(20) . Differences may stem from stigma, social expectations, and mental health literacy.

How does help seeking for mental health problems usually take place, when it does? Models of adolescent help-seeking highlight the complexity of this process. Rickwood et al.(21) describe a sequential process: (1) awareness of symptoms, (2) articulation to a trusted source, and (3) accessing appropriate support. Adolescents exhibit varying approaches to help seeking, from passive or avoidant tendencies to motivated, solution-focused action, shaped by their perception of the causes of distress.(22)

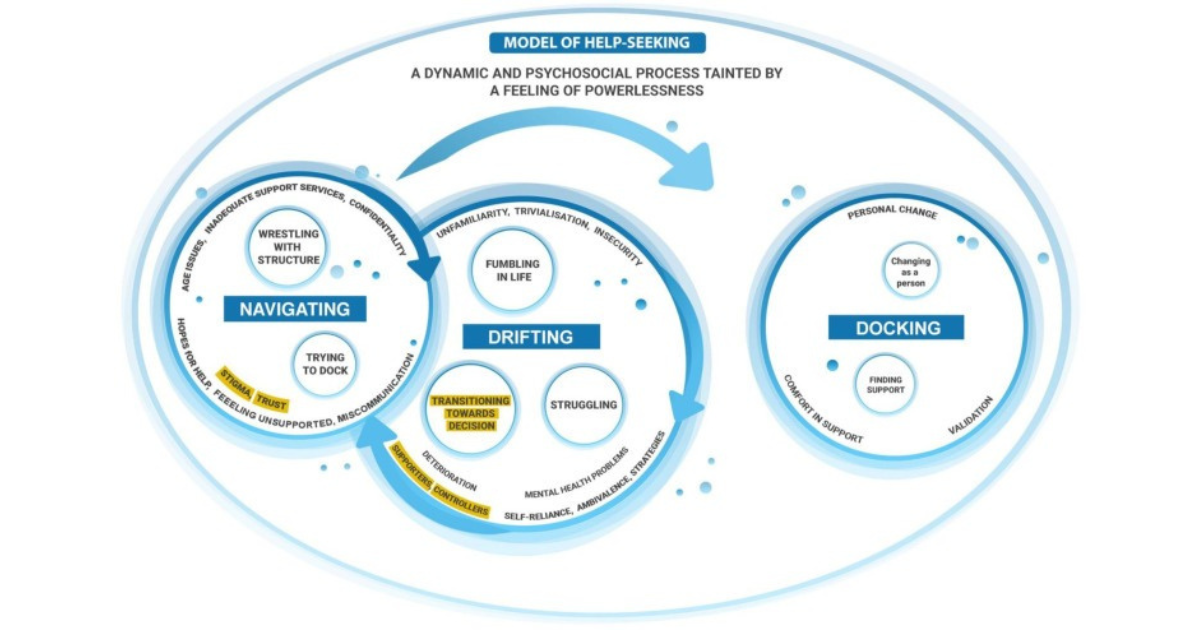

The “Lost in Space” model presents help-seeking as a dynamic, non-linear process across three phases: drifting (uncertainty and lack of knowledge), navigating (structural obstacles and fragmented support), and docking (finding help).(23) This model is a useful framework for understanding help seeking as a fluid, dynamic and psychosocial process across various contexts and cultures.

See diagram of Lost in Space Model below.

Both of these frameworks emphasise the importance of creating safe, supportive environments, addressing structural barriers, and tailoring approaches to individual needs to facilitate timely and effective help-seeking. -

3.3 Barriers and facilitators for support in young people

In this section, we draw on systematic reviews ( 25,26,27 ) and individual interviews ( 28 ) to highlight some of the key barriers and facilitators to connecting young people with mental health support. Barriers can be grouped into four categories: individual, social, systemic/structural, and relational factors involving professionals. Individual barriers—such as low mental health literacy, reluctance to seek help, and preference for self-reliance—are the most frequently reported. Social barriers, including stigma, embarrassment, and peer or family attitudes, are the second-most common impediment to accessing care. Understanding these categories helps identify targets for intervention to improve service uptake and engagement.

Barriers to support for young people

Individual factors:Not knowing where to find help and/or whom to talk to

Failing to perceive a problem as either serious enough to require help or mental health related

Broader perceptions of help seeking:

○ Attitudes toward mental health and help seeking

○ Help seeking expectations

○ Stigma and perceptions about how help seeking reflects their character (i.e. help seeking = weakness in males)Desire to cope with problems on own (common with self harm & depression)

Unsure if problems are serious enough to require help

Problems might improve on their own

Reluctance to attend appointments and adhere to treatments

Doubtful about the effectiveness of professional help

The extent to which help seeking is their own choice (more likely to engage if it’s their choice to seek support)

Preference for informal support

Ability to verbalise need for help and to talk about difficulties

The mental health difficulties themselves posing barriers (i.e. anxiety around attending appointments)

Higher levels of psychological distress, suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms are linked to lower help-seeking behaviours.

Social factors

Perceived stigma, and the experienced or anticipated embarrassment as a consequence of stigma

Negative views and attitudes toward mental health and help seeking within support networks

Anticipated consequences (common are a fear of being taken away from their parents,, losing status in a peer group, making their family angry or upset) Factors related to the relationship between the young person and the professional

Factors related to the relationship between the young person and the professional

Lack of knowledge about confidentiality and disclosure of information

Not comfortable with someone they don’t know well

Less likely to seek help if judged or not taken seriously perceived

Personal or characteristic differences between them and professionals

Professionals invalidating the experiences of young people Systemic and structural factors

Systemic and structural factors

Lack of time, interference with other activities, transportation, costs associated with help

Availability of professional help and waiting times

Complex and inconsistent systems

Difficulty making an appointment

Attitudes of staff toward them

Restrictive entry criteria and intake processes

Mental health resourcing and service provision

Level of systematic orientation toward person-centred care

Facilitators of support for youngpeople

Individual factorsPositive past experiences with seeking help

Past positive experiences using services

Mental health literacy

Social factors

Reduced public stigma and public normalisation of help-seeking

Positive views and attitudes toward mental health and help seeking within support networks

Positive views and encouragement from support networks

Higher engagement with the community

Having a committed relationship with adults like parents, schoolteachers and counsellors (this may assist in the help seeking process)

Factors related to the relationship between the young person and the professional

More likely to seek help if feel respected, listened to and not judged

Similarities between them and professionals Systemic and structural factors.

Opportunity to communicate distress and attend treatment digitally

Quick and easy entry criteria and intake processes

Adequate mental health resourcing and service provision (above article)

Level of orientation toward person-centred care

-

3.4 Implications

Bridging the gap between high youth mental health prevalence and low treatment uptake requires addressing individual, social, and structural barriers while promoting facilitators of help-seeking. Key strategies include:Reducing stigma: School programs, public health campaigns, and accessible resources can normalise help-seeking.

Improving mental health literacy: Teaching young people about mental health, self-help strategies, when to seek professional support, confidentiality, and what to expect from treatment reduces fear and uncertainty.

Embedding services in schools: Locating support within familiar settings lowers cost, travel, and scheduling barriers.

Ensuring service availability: Increased willingness to seek help must be matched by adequate professional provision.

Training adults in adolescents’ lives: Parents, teachers, and mentors need guidance on recognising distress and communicating in ways that support help-seeking.

A coordinated, person-centred approach across these levels can improve engagement and ensure that young people access the care they need.

-

4.1 Parental involvement in access and continued use of mental health services

Help-seeking in adolescents is rarely independent; parents and carers play a central role in identifying struggles, responding to crises, and facilitating access to support. EPIC’s model reflects this reality, positioning parents as critical first responders. Evidence supports this: 94% of Australian adolescents report that others—usually parents—shape their decision to seek help, and in older adolescents, 40–55% rely primarily on family to access clinic-based services.(29) Another Australian study of 30,000 demonstrated that in 40-55% of older adolescents, family was the major influence in receiving clinic-based services.(30) Strong, supportive parent–child relationships - including emotional and physical availability - facilitates help-seeking and improves outcomes, particularly for LGBTQI+ youth, who face heightened stigma and vulnerability.(31)

Parents can also act as barriers to help seeking. Factors such as limited problem recognition, beliefs that difficulties are intentional or “just a phase,” or their own perceived barriers to care can delay or prevent access.(32) Initiatives like “no wrong door” policies help young people access services independently when parental support is limited.

Parental influence extends to the type and timing of care accessed.(33) Adolescents may be motivated, reluctant, or even resistant to help depending on how parents involve them in care - ranging from advocacy and collaboration to restricting understanding of treatment processes. Parents often navigate a complex and arduous system, facing costs, unclear wait times, and multiple referral steps.(34)

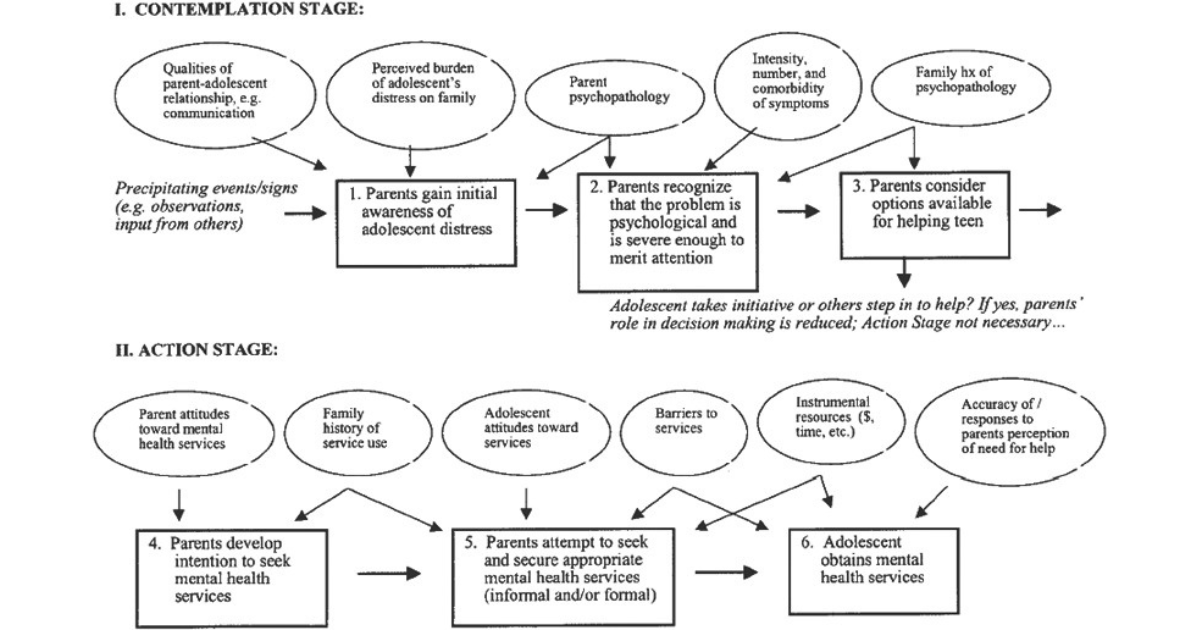

Sociocultural models contextualise parental involvement, highlighting how family, community, and social networks shape adolescent help-seeking. Logan and King’s (2001) parent-mediated pathway model emphasises parental attitudes, cognitions, and availability as key determinants of service access.(35) Whilst a potentially useful understanding of help-seeking as moderated by parents, this model assumes parents will play a key role in the help-seeking process.

See Parent Mediated Pathway Model below.More recent frameworks incorporate adolescents’ readiness, independence, and resource availability, while also recognising the wider contexts of family, available resources and wider social context.

Overall, parental involvement is both a protective and facilitative factor in adolescent mental health care—but also a potential source of barriers. Understanding these dynamics is crucial to improving access, engagement, and outcomes.

-

4.2 Factors that influence parental involvement in care

Parental involvement in adolescent mental health care is shaped by multiple interrelated factors, including beliefs and understanding of mental health, emotional availability, and capacity to navigate the help-seeking process.

Mental health literacy and beliefs

Parents’ knowledge of mental health and help-seeking significantly influences whether and how they support their child. High mental health literacy helps parents recognise symptoms, respond effectively, and facilitate timely access to care.(39) Conversely, limited knowledge, misconceptions about the intentionality of symptoms, or beliefs that difficulties are “just a phase” can delay support, increase stigma, and hinder treatment.(40) Disorders with internalising symptoms, such as anxiety or depression, are particularly vulnerable to being overlooked, whereas externalising behaviours, such as aggression or self-harm, are more likely to prompt parental concern and action. Parent perceptions often shape whether help is sought, highlighting the need for education and awareness programs, especially for parents of gender-diverse or LGBTQI+ adolescents who face additional challenges.(41)

Emotional availability and family dynamics

The quality of parent–child relationships plays a key role. Adolescents are more likely to seek help when they feel heard and supported. Factors such as parental burden, availability, and perception of the child’s needs strongly influence engagement with services (Ryan, Jorm, Toumbourou, & Lubman, 2015). Conversely, dismissiveness, lack of awareness, or requiring a crisis point before intervention can delay care and exacerbate feelings of helplessness in young people.(42) This is particularly true when an adolescent’s disorder presents with less externalising symptoms. (43)

Parental facilitation of help-seeking

Parents also act as navigators and advocates within the mental health system. They may encourage service use, support adherence to treatment, and communicate with professionals on behalf of their child. The degree of collaboration varies, with some parents taking a guided, supportive approach, while others need to assertively direct help-seeking.(44) Challenges arise when parents must interpret and convey their child’s experiences,(45) navigate complex service systems, or manage practical barriers such as scheduling conflicts, appointment locations, and specialist referrals.(46) These logistical difficulties are compounded by busy family lives and limited resources.

Societal and systemic factors

Parental involvement is influenced not only by family factors but also by broader social and systemic contexts. Stigma, mistrust of services, and cultural or religious beliefs can all affect parents’ willingness to engage with mental health services.(47) Access to culturally appropriate, clear, and practical information about services is critical in supporting parents to act effectively.Family relationships and communication

Family relationships, home environment, and communication patterns directly affect both help-seeking and mental health outcomes. Young people’s decisions to disclose mental health concerns are highly situational, shaped by readiness, social context, and anticipated consequences.(48) Being able to confide in family members predicts improved long-term mental health and functioning,(49) but disclosure is often challenging. Adolescents may withhold concerns to avoid worrying parents or being judged, particularly in homes with conflict or trauma.(50) Parenting style, supportiveness, and responsiveness influence disclosure and engagement, while discrepancies between parent and youth perceptions of severity are common.(51) Frequent discussions of symptoms and issues between parents and young people may impact the self esteem of the young person.(52) These communication patterns may also be influenced by desires for autonomy and self-sufficiency.

Communication and relationships evolve throughout the care process. Family engagement in services can strengthen parent–child relationships.(53) Conversely, parental stigma, feelings of inadequacy, or dismissiveness can hinder help-seeking and impact family wellbeing. These findings underscore the importance of person-centered, trauma-informed approaches that support parents and adolescents collaboratively, particularly in complex or high-risk family contexts

Long-term bidirectional effects and co-regulation

Parenting behaviours and pre-existing parental mental health have a bidirectional relationship with children’s mental health. Children of parents with mental illness are at higher risk of developing similar or related mental health issues, reflecting a combination of biological, developmental, and environmental factors.(54) Longitudinal studies indicate that maternal parenting characteristics, such as warmth and consistent discipline, can moderate the trajectory of anxiety in children aged 6–12.(55) An Australian review found that 16–79% of youth receiving mental health treatment had at least one parent with a mental illness, highlighting the prevalence of this dynamic.(56)

Parents influence child outcomes through relationship quality, communication, and parenting practices.(57,58) Support for parents’ own mental health and guidance in maintaining warm, consistent parenting even during stress has strong protective effects for children.(59) Conversely, parental emotion dysregulation can model dysfunctional emotional regulation for children, increasing risk for internalising problems such as anxiety or depression.

Child mental health difficulties also affect parents, contributing to stress, emotional strain, and reduced wellbeing, especially when professional support is limited or waiting times are long.(60,61) This reciprocal influence can create functional or dysfunctional cycles: parental stress and poor emotion regulation may worsen child outcomes, and children’s difficulties may amplify parental stress.(62,63) Factors such as overprotectiveness, sensitivity, or parenting stress can further reinforce these cycles.(64)

Research demonstrates this bidirectionality in both anxiety and depression. For instance, adolescent depression can reduce parental care and responsiveness, while parental depression may exacerbate child symptoms, perpetuating family dysfunction.(65,66) These findings underscore the importance of supporting parental mental health and emotion regulation to break cycles of intergenerational risk, strengthen parent–child relationships, and improve long-term outcomes for adolescents.

-

4.3 Implications

Parents play a crucial but complex role in determining whether adolescents access mental health care. Supportive and informed parents can encourage help-seeking, while stigma, low mental health literacy, or conflicting beliefs may discourage it. Improving parental understanding and communication is therefore essential.

Interventions should build parental mental health literacy, a key service gap that EPIC aims to address. Clinicians should also recognise that parents and adolescents often view or express the same problems differently; exploring these perspectives and understanding both parent and child understanding of an issue early can reduce tension and improve engagement.(67).

Parental emotional regulation is another critical factor. Parents who manage their own emotions well model positive coping and create supportive environments, while those with emotional difficulties may inadvertently reinforce distress in their children. Strengthening parents’ wellbeing—through education, counselling, or peer support—can therefore improve outcomes for both generations.

Overall, interventions should target both adolescents and their parents, promoting open communication, emotional literacy, and shared decision-making in care.

-

5.1 Experiences and goals of care

Care for children and young people (CYP) is an ongoing, dynamic process involving families, carers, and healthcare providers. In Australia, primary healthcare is delivered through GPs, community centres, and private clinics.(68) Chronic or complex conditions, including mental illness, require coordinated approaches addressing physical, psychological, and social needs. Fragmented care can reduce quality of life and increase hospitalisation.(69) Interprofessional collaborative practice (IPCP), where multiple professionals work with families, is recommended, with parents often coordinating care while supporting adolescent independence.(70)

Young people must adapt to frequent changes in diagnoses, care teams, and life circumstances.(71) Effective care models emphasise shared responsibility, collaborative decision-making, and youth autonomy.(72) This can create tension, particularly as adolescents gain medical independence and confidentiality, requiring clinicians to carefully balance support and involvement of parents.

For parents, the goal is to support their child while navigating complex care systems. This role often involves significant personal change, including altered family dynamics, disrupted routines, and shifts in identity.(73) Supporting adolescents through these changes enables engagement and self-management.

Diagnostic systems provide consistency for clinicians but are not the sole measure of care.(74) While reliable, they can pathologise normal experiences, decontextualise difficulties, and lack cultural sensitivity. Holistic alternatives—such as psychosocial assessment, trauma-informed care, stepped care, and attachment-based interventions—offer scientifically valid approaches that better address the full needs of CYP.

-

5.2 The impact of child/adolescent mental health on parents/families:

Caring for a child with a mental health difficulty can be profoundly distressing for parents and carers, affecting their psychological wellbeing, stress levels, and family relationships.(75) Parents of children with mental health issues report higher rates of mental health problems themselves, 51% compared with 23% among parents of children without such issues.(76) Anxiety, depression, guilt, helplessness, and feelings of needing to hide their own support needs are common,(77) with parents of young people who self-harm reporting particularly high levels of distress.(78) These challenges are compounded by difficulties navigating healthcare systems, including long wait times, scarcity of services, and experiences of judgement or stigma, which can reduce engagement with care, impair daily functioning, and strain family relationships.(79)

Mothers are often most affected, given their central role in childcare and service access, though fathers also experience elevated stress and mental health symptoms.(80,81) Both parents should be engaged in care to ensure that the support provided reflects the needs of the entire family, but research highlights a gap in understanding fathers’ experiences and wellbeing.

A 2025 systematic review highlighted four key areas of impact on parents:(82)

Practical and financial demands – Long waits, service scarcity, and caregiving responsibilities limit time for social, domestic, and work activities, contributing to financial strain and fatigue.

Family dynamics – Parents frequently shift into a “carer” mode, monitoring their child and adjusting their own behaviour to avoid conflict. Misunderstandings about child behaviours can generate relational conflict, both between parents and within the wider family, sometimes leading to neglect of siblings.

Emotional burden – Parents experience anxiety about safety, relapse, and stigma, along with trauma, chronic stress, and fears about the loss of their child’s future. Internalised stigma and guilt may manifest as social withdrawal.

Self-care challenges – Parents often prioritize the child’s wellbeing over their own, seeking help only in crises. Peer support and confidential spaces for sharing experiences are highly valued.

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) exemplifies the emotional toll of supporting a child with mental health challenges. As such, there is a large body of research on NSSI’s impact on parents, one model of which is presented here. Parents experience self-blame, selective disclosure, isolation, and anticipatory concerns about their child’s reactions, highlighting the interplay between parental beliefs, coping strategies, and parenting behaviours.(83,84)

These factors are equally relevant to other mental health conditions, highlighting how parental beliefs and wellbeing are influenced by stigmas surrounding their young person’s disorder and the demands of caregiving.

Overall, parental mental health, beliefs, and self-care are critical determinants of family functioning and child outcomes. Supporting parents through education, counselling, peer networks, and targeted interventions is essential to promote both parent and child wellbeing.

-

5.3 Interventions to improve outcomes for parents or carers

Recognising that parents and carers require support, information, and resources, a growing body of literature has explored interventions to improve parental wellbeing. Interventions are varied, targeting different outcomes, but psychoeducation is the most common, reflecting the need to increase parents’ knowledge of mental health and how to support their children effectively.(85) Other interventions include cognitive behavioural therapy, family therapy, coping and communication strategies, and parent skills groups embedded in DBT programs for children who self-harm or experience suicidal behaviours.(86) These programs aim to reduce caregiver distress and improve family functioning.

Group-based “parent training” programs have shown short-term improvements in parental depression, anxiety, anger, confidence, and relationship satisfaction,(87) although effects often diminish by six months and are largely untested for parents of children with mental health difficulties.(88) Systematic reviews highlight challenges in measuring outcomes due to variation in intervention focus, parental involvement, and complexity of parent-child dynamics.(89) Families with complex relationships or parents experiencing their own mental health difficulties may require tailored interventions addressing both parental and child needs simultaneously.(90)

Family-based interventions focusing on relational dynamics, such as addressing the impact of child anxiety and depression on family relationships, have shown effectiveness.(91) Typically, these programs treat families as both recipients of support and co-therapists for their children, though research is limited regarding long-term outcomes for the whole family. Greater understanding of factors influencing parental wellbeing is needed to inform effective interventions.

Peer Support Programs

Peer support programs, such as EPIC, play a critical role in supporting parents and carers of young people with mental health challenges.(92) These programs reduce isolation, promote self-care, and help shift beliefs around self-blame.(93) They often combine educational, social, and acceptance-based approaches, offering a safe space for parents to share experiences without stigma.

Research on peer support programs highlights several outcomes:(94)

Parents regain agency, clarify their identity, and prioritise their own wellbeing.

Transparency and shared experiences reduce isolation and provide emotional validation.

Practical guidance, including communication strategies and service navigation, prevents crisis escalation.

Flexible delivery (e.g., Zoom, phone, messaging) increases accessibility for parents with demanding schedules.

Holistic support can connect families to broader resources, including healthcare, education, and social services.

Program design factors critical to success include early engagement, flexible communication, appropriate peer training, supervision, and ongoing support to prevent burnout. Peer supporters require training to manage complex conversations and boundaries, supported by supervision from mental health professionals and peer networks.(95)

Overall, evidence suggests that parent-focused interventions, particularly peer support programs, are effective in improving parental wellbeing and capacity to support their child, while highlighting the need for flexible, responsive, and holistic approaches.

-

5.4 Support needs and gaps

Systematic reviews highlight several recurring support needs for parents and carers of children with mental health difficulties.(96,97,98)

Informational support is a primary need. Parents require clear guidance on the mental health condition, available services and legal considerations, adolescent development, parental roles, behaviour management strategies, and how to adapt family dynamics after diagnosis. At the point of diagnosis, parents often experience information overload, followed by periods of insufficient guidance. Many parents seek information independently, risking exposure to misinformation and increased distress. Reliable resources—online or through programs—can reduce uncertainty, self-blame, and provide practical strategies.

Validation and social support are also critical. Parents frequently experience isolation and stigma, and seek support for managing their emotions, coping with barriers to services, boosting parental self-efficacy, and connecting with broader networks to share experiences. Programs that normalise parental emotions and experiences help alleviate isolation and empower caregivers.

Communication with professionals is a key gap of support in many cases. Parents often report feeling disregarded or judged by healthcare providers, particularly regarding eating disorders, anxiety, and OCD. They desire communication that validates both their distress and their child’s, and empowers them to participate in care. Similar challenges exist in educational settings, where schools may only engage during crises and may lack knowledge of conditions like OCD or anxiety, leaving parents to coordinate support.

Practical and systemic support is also needed. Parents value rest, opportunities to focus on their own wellbeing, financial support, equitable and adapted schooling for their children, and family-centred services that are respectful, qualified, and accessible. The Australian Government is currently developing a National Carer Strategy to recognise the contributions of parents and carers. Recent AIFS reporting provides an evidence base highlighting the supports needed to reduce strain, improve parent wellbeing, and better equip caregivers in supporting young people with mental health challenges.(99)

-

5.5 Clinical implications of needs

The following key priorities and implications align with EPIC’s mission to equip parents with knowledge, support, and community connection:

Supporting parent wellbeing and mental health is a priority

Support for parents and parental self care is vital. Supporters and clinicians should routinely check in with parental wellbeing, and provide signposting to appropriate sports such as peer support groups, psychological support or mental health specific parent training programs. These interventions can target parents’ emotion regulation and self-compassion can break intergenerational cycles of distress and improve both parent and child outcomes.

Enhancing parent knowledge and literacy

Low mental health literacy is a barrier for parental acceleration of the help seeking process, and many parents feel ill equipped to understand or navigate their child’s care particularly when facing stigma or misinformation. Clinicians and support groups should offer accessible, credible and vetted information for education and seek to normalise help seeking for parents and families. This is particularly true when it comes to parents of children who are transgender or gender diverse, as these groups deal with an incredible amount of stigma. Important education aspects should include:

Information about symptoms, confidentiality, and care pathways;

Guidance on communication with CYP about sensitive issues (e.g., self-harm);

Information on how to access and collaborate with services.

Challenging societal pressures and expectations around parenting and mental health

Facilitating family communication

Family communication patterns and relationships can maintain or exacerbate CYP mental health problems. Services and clinicians should incorporate families into programs and foster open communication, validation of emotions and include them in treatment planning while balancing adolescent autonomy.

Building peer and community supports

Isolation, shame, embarrassment and self-blame are common amongst parents and carers. Peer support can reduce this, normalise parental emotions and create the space to share experiences. Community based programs should be prioritised and developed. This fosters empowerment, sharing of resources and strategies and reduces stigma.

Integrated care

Services should provide holistic and integrated pathways of care that give parents the options to consider different treatment pathways, ensure the health and wellbeing of their entire family, and consider financial and occupational challenges.

Training for healthcare and service providers

Services should prioritise engaging with parents as well as children. Similarly, school-based programs can play a vital role by improving staff understanding of mental health and creating consistent channels of communication with families. Clinicians and services can strengthen families by providing consistent, clear communication, family-inclusive care, and psychoeducation that increases parental confidence and mental health literacy where needed.

-

EPIC’s approach aligns closely with evidence-based recommendations for supporting families: integrating psychoeducation, peer connection, and accessible services helps reduce parental stress and improve their capacity to support adolescents. By providing both in-person and online options, EPIC meets families where they are, addressing barriers such as isolation, limited mobility, or time constraints. The organisation’s focus on crisis support, emotional validation, and practical guidance complements formal mental health services, operationalising research findings into real-world impact and strengthening the parent-adolescent support system.

EPIC’s programs and activities provide practical support to parents navigating the mental health challenges of their children. Parent feedback highlights common needs identified in this research report: reliable information about mental health conditions and services, emotional support, and guidance for advocacy and care coordination. Parents reported feeling isolated, overwhelmed, or uncertain, and emphasised the value of connecting with others who understand their experiences. Testimonials illustrate how participation in EPIC walks, online meetups, and peer support create an accessible program that reduces isolation and builds parent confidence in managing their child’s care and service access journey. For example: "EPIC helped my family at a very difficult time, listening and remote support workshops are very helpful for working families"

Across 2025, EPIC reported 1,511 peer support connections, 387 walk participants, 192 online participants, 43 promotional campaigns, and 13,649 website visits, illustrating its broad engagement and reach. -

Services

Integrate family inclusive practices; in assessment, treatment plans and recovery

Adopt parent psychoeducation in youth care; Equip parents with knowledge about adolescent development, common mental health conditions, and strategies for communication and co-regulation.

Reduce barriers to access; expand low cost, culturally safe entry points into care

Enhance mental health literacy

Families

Promote coregulation and open dialogue

Support parents to manage their own emotional responses and model healthy coping

Increase mental health literacy (credible, evidence based information)

Build support networks

Policy and Advocacy

Advance mental health literacy campaigns to combat stigma

Address access inequities

Prioritise funding for health models that recognise parents as carers and legitimate treatment components for young people

EPIC

Expand resources for parents around mental health disorders, integrate parent experiences and recommendations for service access pathways into online resources

Collaborate with service providers and policymakers; EPIC has resources and insights from their parent network to help inform system-level changes and advocate for family and parent-centred care

-

1 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3022639/

2 https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/latest-release

3 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3022639/

4 https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/latest-release

5 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10577900/

6 https://headspace.org.au/assets/Uploads/Increasing-demand-in-youth-mentalh-a-rising-tide-of-need.pdf

7 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11934408/

8 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10786006/

8 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10786006/

9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25649325/

10 https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-03/annual-report-2013-14.pdf

11 #

12 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10406047/

13 https://youngmindsmatter.thekids.org.au/siteassets/media-docs---young-minds-matter/survey-user-s-guide-final.pdf

14 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10826-022-02498-5

15 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23248576/

16 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673607603705

17 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8835517/

18 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jan.12423?saml_referrer

19 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28719230/

20 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31215327/

21 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17908023/

22 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10578439/#s5

23 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7542338/

24 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7542338/

25 https://acamh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jcpp.12398

26 https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-244X-10-113

27 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7291482/

28 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740922003966

29 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25886609/

30 https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-015-0429-6

31 https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/population-groups/lgbtiq/overview

32 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/educational-and-developmental-psychologist/article/abs/parent-helpseeking-behaviour-examining-the-impact-of-parent-beliefs-on-professional-helpseeking-for-child-emotional-and-behavioural-difficulties/5F9D1DBD3AAA091BAD775617930BD6E8

33 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740922003966#b0035

34 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.5172/jamh.2013.11.2.131

35 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1093/clipsy.8.3.319?saml_referrer

36 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1093/clipsy.8.3.319?saml_referrer

37 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2158244018807786

38 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2158244018807786

39 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1521/suli.2008.38.1.60

40 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00012.x?getft_integrator=sciencedirect_contenthosting&src=getftr&utm_source=sciencedirect_contenthosting

41 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740922003966#b0150

42 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0004867412441929#bibr12-0004867412441929

43 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0004867412441929

44 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2158244018807786

45 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33741575/

47 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12310-015-9152-1

48 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29205343/

49 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212657017301204

50 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740922003966#b0150

51 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10964-019-00994-4

52 https://adc.bmj.com/content/106/11/1125

53 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0190740922003966#b0035

54 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26445808/

55 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20423547/d_Interactions_Implications_for_Research_and_Practice

56 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32133563/

57 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10826-013-9781-7

58 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34255922/

59 https://aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/2003_childrens_social-emotional_wellbeing_paper_0.pdf

60 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33839559/

61 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38302408/

62 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33839559/

63 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326425975_Emotion_Regulation_Dynamics_During_Parent-Child_Interactions_Implications_for_Research_and_Practice

64 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/development-and-psychopathology/article/bidirectional-associations-between-parenting-stress-and-child-psychopathology-the-moderating-role-of-maternal-affection/0741691FD30B360367BDC1933B2EE273

65 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9240277/

66 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21735051/

67 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0004867412441929

68 https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/7c42913d-295f-4bc9-9c24-4e44eff4a04a/aihw-aus-221.pdf

69 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7783195/

70 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/framework-for-action-on-interprofessional-education-collaborativepractice

71 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11091539/#s11

72 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5457360/

73 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10632645/#hex13828-sec-0190

74

https://aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/1805_cfca_diagnosis_in_child_mental_health_0.pdf

75 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26421058/

76 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22140301/

77 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11298743/#R16

78 https://acamh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/camh.12692

79 https://adc.bmj.com/content/106/11/1125

80 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10578-018-0822-8

81 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10826-015-0230-7

82 https://mentalhealth.bmj.com/content/ebmental/28/1/e301518.full.pdf

83 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4586015/#CR15

84 https://acamh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/camh.12692

85 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11425941/

86 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37510567/

87 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10898322/

88 https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.5243/jsswr.2013.20

89 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34537101/

90 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11425941/

91 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28374218/

92 https://acamh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/camh.12692

93 https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(22)00167-5/fulltext

94 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10577900/

95 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40335988/

96 https://mentalhealth.bmj.com/content/ebmental/28/1/e301518.full.pdf

97 https://www.psychiatricnursing.org/article/S0883-9417(17)30005-5/abstract

98 https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(22)00167-5/fulltext#sec-4

99 https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2025-07/australian-institute-of-family-studies-scoping-review.pdf

(Lost in Space Model)(24) - Described in 3.2, Current access to care, Adolescents and help seeking

(Parent Mediated Pathway Model)(36) - Described in 4.1, Parent influence on adolescent help seeking.

With gratitude

EPIC thanks the author, Mark Campell, who provided this research essay as part of his internship through the Macquarie University PACE Program, for his thoughtful contribution and dedication. Marks work shines a light on the importance of empowering parents so they are equipped with knowledge, strategies, their children hve a better chance of recovery.

Go to the EPIC Mental Health resources page for the following information:

Emergency contacts

Organisations that support young people and their families

Websites with useful information and strategies to support young people

Podcasts/Videos with useful information and strategies to support young people

Support groups for parents/carers caring for young people

Apps for young people

Never miss an EPIC event, resource, sign up for the EPIC newsletter here: